ST. B. EDMUND

CAMPION, S.J.M.

BRUNN, BOHEMIA

1571

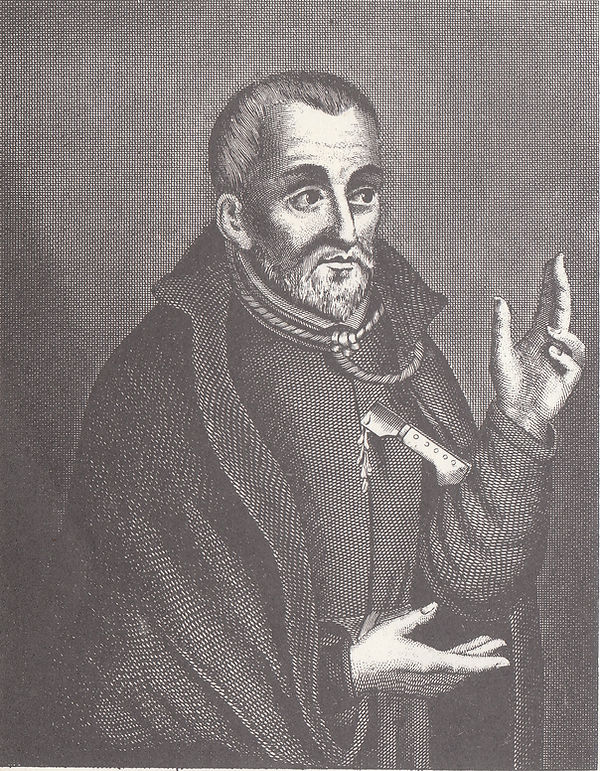

St Edmund Campion SJ

Jesuit Priest and Martyr, 1540 - 1581

This is the earliest known portrait of Campion completed in the year after his execution.

Mary, dear Mother of our God,

Sweet flowers we bring to thee,

Upspringing from the willing sod,

Types of thy purity.

Protect us from the world’s foul breath,

Great Queen Immaculate.

In joy and sorrow, life and death,

Be thou our advocate.

- A. de Lande

The busy whirl of cabs and omnibuses, of carts and carriages, that eddies round the Marble Arch, the ever-changing crowds that surge by, make us forget that there we are on holy soil. Three hundred years ago, Tyburn reared its three-legged gibbet close by, and the blood of martyrs ran freely beneath it for the cause of God and of His Church. Now that the Church has, by public act, recognized these her valiant sons, it is well to make known their heroism, that God may be glorified in them, and that men may pay honor to whom honor is so rightly due. Among the many who died there, and to whom the Holy See has decreed the title of Blessed, was a priest of the then new-born Society of Jesus, the first of his brethren to shed his blood on an English scaffold. His life is full of interest, as it is full of lessons not only for his brethren, but for all the household of the faith, and even for those who are outside.

Edmund Campion was born within the sound of Bow bells, in the year 1540. He was the son of an honest Catholic bookseller. It was a year of grave events. The dissolution of the greater monasteries, in England, by Henry VIII., was another step towards the destruction of her ancient faith, while the solemn approval by Pope Paul III. of the Society of Jesus, was a promise of help near when danger was greatest. The boy would have been apprenticed to a trade, if his bright wits had not won for him the interest of one of the great city companies, who sent him to the well-known Blue Coat School. There was plenty of rivalry in those days between the scholars of the different grammar schools; and, in the inter-scholastic contests, young Edmund came so well to the fore, that, when Queen Mary entered London in state, on her obtaining the English crown, he was chosen, though but a lad of thirteen, to make a set speech to her as she went by. The Lord Mayor of London, on that occasion, was good Sir Thomas White; and no wonder, when he re-opened, as a lay college, the Cistercian House of St. Bernard, at Oxford, that a place was found in the new St. John’s for this promising youth. No wonder, too, that Edmund soon became a special favorite of the founder, and made his mark in the University. But that rapid success was a serious danger to his soul.

The University Church of St Mary the Virgin, Oxford

Campion was a student, tutor and fellow in the University of Oxford and would frequently have worshipped at the University Church.

Queen Mary’s short reign was over, and her base-born sister, Queen Elizabeth, quickly showed how hypocritical had been her profession of Catholicity, and how resolved she was to follow in the footsteps of her father. The readiest speaker in Oxford, Campion was called upon by the Queen’s too fervent favorite, Dudley, to deliver a funeral oration over the body of his murdered wife, poor Amy Robsart, whose fate is familiar to the readers of Kenilworth. Edmund’s friend and protector, Sir Thomas White, was dead. He had died a staunch Catholic; and though Edmund made over him a panegyric, eloquent as it was sincere, yet he had found a still more powerful friend in Dudley, whom Elizabeth, in her shameless passion, had raised rapidly to honors and afterwards made Earl of Leicester, and whom the University, to flatter the royal lover, elected as Chancellor. Campion never doubted the truth of the Catholic faith, but like many before and after his time he could not bring himself to sacrifice his splendid prospects by open confession of an outlawed creed. He was the star of all the gay pageants and learned discussions by which Oxford entertained the Queen on her visit to the University. Cecil, her Prime Minister, was forward with promises of patronage and support.

Campion unhappily allowed himself to be persuaded into receiving the deaconship in the new state religion, as a necessary step to preferment. But his mind found no rest. God clamored for his soul. He sought for excuses for his outward conformity. But the more he sought, the more clear proofs did he discover that the old faith alone was true, and that the new was false. In vain had he looked to Scripture or to the ancient church. They both declared against him. He talked out his difficulties with too many for his doubts to be long a secret, and the Grocers Company, from whom he held his fellowship, insisted that he must make a clear profession of Anglicanism at the well-known pulpit of St. Paul’s Cross in London. Others there were of his friends who had sacrificed all for God, and one of these, Gregory Martin, quondam tutor to the ill-fated and heroic Earl of Arundel a brilliant scholar of St. John’s wrote from beyond the seas urging him to come out of the peril and snare.

Book used by Edmund Campion while a scholar at Oxford University

This book, from 1484, is a commentary on Aristotle's Physics. There are three signatures of Edmund Campion on the flyleaves showing it belonged to him during his time at Oxford. The book was given to Campion Hall at its foundation in 1936.

It was a snare for Campion was made Proctor and Public Orator of the University, and so raised as high in office as one could be, before taking his degree of Doctor. Young men imitated his style of writing and of speech, his very dress and mannerisms, and gloried in being called Campionists. One of these was Richard Stanihurst, whose father was a good Catholic and yet Recorder of Dublin and Speaker of the Irish House of Commons. In Ireland and in the house of Mr. Stanihurst, Campion at last determined to take refuge. There he hoped to be safe to follow the Catholic faith, under such powerful protection. At the same time he was anxious to have a hand in setting up again the ancient Catholic University of Dublin, which like so many other seats of learning, had been utterly ruined by the change of religion. The Lord Deputy of Ireland, Sir Henry Sydney, as well as the Lord Chancellor, if anything favored the old religion. So being then about twenty-one, Edmund settled down quietly in the Recorder’s house in Dublin, where, surrounded by books and immersed in study, he led so strict and so holy a life that the good Irish folk called him the angel.

St Edmund Campion SJ

Early 18th Century Italian (?)

This portrait was recovered from Augsburg Cathedral in 1889. It had probably hung in one of the German Jesuit Colleges until the Supression of the Society in 1773 when libraries and artworks were confiscated. It now hangs at Campion Hall Oxford.

But the storm-clouds were every day gathering thicker and thicker. The persecutions of Elizabeth and her cruelty to her captive guest, Mary Stuart, found their answer in the ill-starred rebellion of the North. Philip II., always dilatory, was planning an invasion of Ireland, in the name of St. Pius V.; and in a paroxysm of rage and terror, fresh measures were adopted by the Queen against the Catholics. Sydney was on the eve of leaving Ireland, and could thus offer no further protection to Campion. One good turn, however, he did for Edmund. He gave him secret warning of his peril, and Campion fled at once through the darkness of night to Sir Christopher Barnewall, at his home in Turvey, where he was hidden away in a garret. It was his first taste of suffering for the faith. However, he continued to devote himself to literary work, and wrote in his narrow cell an interesting sketch of Ireland as it then was. An old serving woman coming into his hiding-place, during the very day on which he got there, to tidy up, thought the poor stowaway was an apparition, and ran off to tell Lady Barnewall that a ghost was in the garret, writing a book. She got well laughed at for her pains. But the search for Campion was so hot that he felt his stay endangered his kind hosts; so he took ship for England, disguised as the servant to Lord Kildare’s steward, and under the name of Patrick, out of devotion to the great Apostle of Ireland.

The officers searched the ship for him, and he stood by, as with big oaths they cursed the villain Campion who had again escaped them, he all the while praying heartily to his new name sake to shelter and defend him. Edmund found England far too perilous for him. Still he dared to be present in court during the trial and condemnation of the aged martyr, Blessed Dr. Storey, who had been kidnapped in the port of Antwerp, and against the law of nations brought over to England, where he was tried, and suffered the death of a traitor. The trial was conducted with such disregard of all law and justice, that Campion felt that as a layman he could do little for the progress of the faith, and hastened to rejoin a number of his old Oxford friends, who had sought in a university in a Catholic land for opportunity of pursuing their divinity studies and preparing themselves for the priesthood so as to keep alive the Catholic religion at all cost in their dear fatherland. Two Oriel men - Dr. Allen, the future Cardinal, and Dr. Oliver Lewis, afterwards Bishop of Cassano - and a host of others, had founded an English college at Douay, in Flanders, the nursing-mother to be of so many martyrs, confessors and apostles. There, by affiliation to the university of that town, - whose Chancellor, Dr. Smith, was himself an Oxford man, -higher education could be obtained for the English exiles; and thither young men and old flocked from our shores to fill up the glorious regiment of saviors of their country.

London Bridge

Note the heads of martyrs on long spiked poles at the entrance to the bridge. This barbarity was to deter others from Catholic activities

The very day of Dr. Storey’s cruel death, Campion was crossing the Channel, when his vessel was overhauled by an English frigate, and the passengers were asked for their passports. Edmund naturally had none, so he was carried off by the captain of the "Hare," who put into his own pocket the money which Campion’s friends had collected for his journey, and threatened to take him to London. But on the way from Dover to town it became pretty clear that he preferred Campion’s purse to Campion’s prosecution, so dropping gradually behind his captor, who evidently was not at all anxious about his charge, Campion soon parted company with him, and once more put the sea between him and his well-loved country. Cecil complained to young Stanihurst that England had lost in Campion one of its diamonds. And that was in the very days of Shakespeare!

St Edmund Campion SJ

Engraving Antwerp 1631

A year of peace, but not of idleness, went by in the quiet of Douay. Campion finished his theological studies and took the degree of Bachelor of Divinity, while giving lectures at the same time in the English College. The new Chancellor of the University, a Fleming, who heard him speak on St. Michael’s day, was forced to admit that his country could not show a genius like to him. But more than this, Edmund ascended the first steps on the altar, receiving the four minor orders and the sub-diaconate. He was then thirty-one. But his heart was not even yet at rest. What he called "the abomination of the sign of the beast," the Anglican deacon’s orders, which he had received at Oxford, called for the expiation of penance. At his first coming to Douay he had made a complete offering of himself, of his life and blood to His Lord and Master for the land he loved. A voice within him urged him, as it had so many before and after, to go in a penitent spirit to the Holy City, and there, by the favor of the two great Apostles, to seek admission into the Society of Jesus. He made no reserve in his obedience, leaving his future in the hands of God; but still he resolved, in case he were received, to beg his superiors to grant him the wish of his heart, and to allow him to spend himself and be spent for the restoration of the faith in England. And before he started on his journey, he began his apostleship by urgent letters of farewell to some of his old friends, Catholic and Protestant, so full of power, that many were induced to follow his example of leaving home and all to follow Christ. Among those to whom he wrote was his old friend, the aged Anglican Bishop of Gloucester, whom he had known and loved - Cheney, whose views were far apart from those of the other so-called bishops of Elizabeth’s new-fangled hierarchy, and from the fanatical clergy subject to him. He was like a High Churchman of our time, believing neither in the Calvinism nor the Lutheranism of his days, and yet professing, illogically, to stand by Councils and Fathers, though, as his young friend clearly saw, both condemned his position in an heretical and schismatical body. This letter which still exists, as Fr. Persons says, "doth so rattle up the old man of 60 years old (but yet with great modesty, and show of reverence and hearty good will) as it may easily appear how abundantly God has imparted His Holy Spirit unto him, for his letter is truly apostolic."

Many were the friends who came out with Campion to the gates of Douay, to bid him good-bye, as he went on the road, trodden by many a Saxon king and English Saint, to the Apostles Shrine. And, like them, his only retinue was poverty. Begging alms by the way, he met, coming back from a tour in Italy, "an old acquaintance that had known him, in times past, in Oxford in great pomp and prosperity of the world." The English gentleman rode by without recognizing the poor pilgrim, but something in his looks struck him and he turned back, recognized Edmund, and leaping from his horse shook warmly his old friend’s hand, pitying him deeply because sure that he had fallen among thieves. But he was very disgusted when he found that it was only a case of practical following of Gospel counsel. However, he held out his purse and told him to take what he wanted. But Campion would have nothing, and, so Persons tells us (he himself was then at the University), "made such a speech unto him of the contempt of this world and eminent dignity of serving Christ in poverty, as greatly moved the man, and as also his acquaintance that remained yet in Oxford, when the report came to our ears."

It was late in 1572 when Campion reached Rome. Worn out with his embassage to Spain in the suite of the Pope’s nephew, St. Francis Borgia, quondam Duke of Gandia, and at that time General of the Society of Jesus, died on his return to Rome, shortly after Edmund’s arrival. Once there, he needed a long delay before he could present himself for reception to the General, as the electors had to gather in from the foreign provinces of the Society to choose a successor. Nor was it till April 23, of the following year, that Father Everard Mercoeur (Latinized into Mercurianus) of Liege was elected.

Campion was the first postulant received by the new General. The official examiners were so completely satisfied with his answers that he was received as a novice without any further probation. No doubt their previous knowledge all went to confirm their decision. In fact he had come to be so well known by the various Provincials and Fathers, deputies for the election, -there was then no English Province, - that there was a contest over him, as to which should secure his service. Campion rejoiced to think that his lot was now entirely in God’s hands, and his only prayer, and an earnest one, was, that He would, through his superiors, dispose of him when and as He willed. The Austrian province won the day, and Prague in Bohemia was chosen as the place of his novitiate. Thither wards he traveled in the summer, on the close of the Congregation, in company with Fr. Maggi his Provincial and several German and Spanish Fathers, as far as Vienna. Thence he started for the novitiate with Father James Avellanedo, the confessor to the Empress, a man who had held weighty posts in Europe and India, and who told Fr. Persons in after years "how exceedingly he was edified with the modesty, humility, sweet behavior and angelic conversation of Campion which made him ever after to have a great affection for our nation."

Bohemia, the home of the Hussites, had then well-nigh lost its faith: and as John Huss owed his socialistic and anti-Catholic ideas to Wycliffe, Campion felt that as an Englishman he might by God’s holy providence gain some souls in that land back to the faith, "in recompense of so many thousands lost and cast away by the wickedness of Wycliffe." The novice by his fervent life gave great edification to all, for his only thought was to serve God and to live in peace and charity with all around. In two short months the novitiate was moved, on October 10, 1573, to Brunn in Moravia, where things were worse even than in Prague, and where the Bishop hoped that a house of prayer and penance might effect a change for the better. There Fr. Edmund spent a year’s novitiate. One of the novice’s duties was to catechize in the neighboring hamlets. The results were great; but Campion was ever noted as the most successful, and he won many converts to the truth.

In spite of the humiliations and hard life of a Jesuit novitiate, or, rather, because Campion had thoroughly caught the spirit of a true companion and imitator of his Divine Lord, love made all that labor light. The blessed martyr, writing to his former fellow novices, shows how he valued the trials of his probation. "Beautiful kitchen, where the Brothers fight for the sauce pans in holy humility and charity unfeigned! How often do I picture to myself one returning with his load from the farm, another from the market; one sweating stalwartly and merrily under a sack of rubbish, and another under some other toil! Believe me, my dear brothers, that your dust, your brooms, your poles, your loads are beheld with joy by the angels, and get for you from God more than if they saw in your hands scepters, jewels, and gold in your purses." Father Campion’s novice-master was made Rector of a College of Prague, and on September 7, 1571, he went to his new post taking with him his favorite pupil. Amidst the prayerful retirement of Brunn the future martyr had been favored with a vision of Our Lady under the stately and venerable type of St. Luke’s painting at St. Mary’s Major’s, of which a copy was in the novice’s chapel. She offered to him a purple robe as a promise of his victory.

In the College of Prague, Edmund’s talents were at once brought into play. He was made professor of rhetoric to the young gentlemen and nobles of Bohemia, while other humble duties were assigned to him in-doors. He had to be the first out of bed at a very early hour of the morning, to call the community, and had to be the last up at night to see that all lights were out, and that all had retired to rest, while his recreation was often spent in helping the cook in the kitchen. The following year, 1575, when he had taken his first vows, he set up the Sodality of Our Lady among the students, and the year

after he was moved into the convictus or boarding school, and was appointed prefect of discipline, in addition to other duties. Never was he known to make any other difficulty to his superior, when he laid any new labor upon him, but only: "Does your reverence think I am fit to discharge that office?" If the superior said "Yes," he accepted it without more ado. And his companions thought it a miracle that one man could bear so many loads.

Amidst all his varied occupations, Blessed Campion’s fall at Oxford and his reception of Anglican orders was ever a source of trouble to him. And it was in vain "to tell him, that which he knew right well himself, that it was no order or character at all, seeing that he that gave it to him was no true bishop, and had no more authority than a layman, and that indeed these bishops themselves did not consider that any character was given, as in Catholic ordinations, by imposition of hands." Still, the very memory of this mark of his open apostacy made him sad and unhappy. Nor was he ever freed from his inward grief, till the absolute order of his General came from Rome, not to trouble himself about this scruple, and, in 1578, he was ordained deacon and priest by the Archbishop of Prague. He said his first Mass on Our Lady’s birthday.

Meantime news from Rome renewed all his old desires to labor directly for his native land. The blood of martyrs had begun to flow in England. Blessed Thomas Woodhouse, an old Marian priest, had given his life for the faith at Tyburn. Blessed Cuthbert Mayne, the first of the illustrious band that came from the English seminaries across the water, was martyred at Launceston, on November 9, 1577. He was of St.

John’s College, like Campion, and was one of those whom our blessed martyr had persuaded by letter to throw up his position, and to come out of England to Douay. Campion learned, too, that several of his old Oxford friends had entered the Society of Jesus in Rome, of whom the best known are Robert Persons of Balliol, his biographer and future companion, Henry Garnet of New College, and William Weston of All Souls, all three of whom were in turn to be Superiors of the Society of Jesus in England.

Every day the Queen and her advisers grew more angry as the arrival of fresh priests became known, and several captures of Catholic priests called for more care and watchfulness. London had become too hot to hold them. As soon therefore as Father Persons returned, a meeting was held in a small house in Southwark to settle some grave questions before they separated. Several priests and laymen were present. The chief question to be discussed at the meeting was how to rebut the accusation which had gone abroad that the Jesuits had come into England for political and revolutionary ends. It was thought enough to be prepared to deny the allegation solemnly and on oath; but just when the Fathers were bidding each other goodbye at Hoxton, before leaving London, Mr. Pound, a gentleman of rank, came deputed by the many Catholic prisoners in the Marshalsea prison, to urge in their name that some more definite measures be taken, to contradict the rumor. He begged that a declaration written by each Father, signed and sealed, should be left in the hands of some trusty friends, to be produced and published if, after their death, these falsehoods should be urged against them. Father Campion, taking a pen in his hand, wrote upon the end of a table in less than half an hour the declaration which was to play hereafter so important a part. Written off without any previous study, while his friends were waiting his departure, it was so pithy, both for matter and language, as to please greatly the unprejudiced reader and sting his opponents. In it he challenged a discussion on religion before the Council to show how it affected the State, before the University to prove its truth, and before the men of the law to show how the English statute book itself justified his creed. He offered even to preach before the Queen. At the same time he declared that his holy calling and the orders of superiors warned him from any matters of State. Father Campion gave a copy to Mr. Pound; the other, which he kept for himself is now carefully treasured at Stonyhurst College. Pound showed his to other friends, who begged to be allowed to transcribe it, and quickly it became spread about, and fell into the hands of friends and foes alike, and more than one copy was laid before the Queen’s Council.

At once fresh and sweeping measures of persecution were adopted, and the Catholic gentry were packed into the state prisons; and, when these were full, castles, whose ruinous state made them unfit dwellings for men, were crowded with the best and noblest of the land. Meanwhile, well provided with horses, money and changes of disguise by the devotion of the Catholic Association, Fathers Campion and Persons bid each other good-bye, and set out each on his separate mission, full of peril, as it was full of profit. Each was accompanied by a trusty squire, who shared his danger and served as guide. Blessed Edmund passed through Berkshire, Oxfordshire and Northamptonshire, calling at gentlemen’s and noblemen’s houses, both Catholic and Protestant. "We entered, for the most part," Persons narrates, "as acquaintance or kinsfolk of some person that lived within the house, and when that failed us, as passers-by, or friends of some gentlemen that accompanied us; and after ordinary salutations, we had our apartments, by the Catholics’ aid, in some retired part of the house, where putting on our priests’ dress, which we always carried with us, we had secret conference with the Catholics that were there, or such of them as might conveniently come, whom we always caused to prepare themselves for confession late that night. Next morning very early we had Mass, and the Blessed Sacrament ready for such as wished to communicate, and after that an exhortation which had been prepared on horseback, and then we made ourselves ready to depart again." When they were able to prolong their stay, they would repeat these exercises. Such was the plan the Fathers followed.

Once more they came back to the south. Campion was so hotly sought after that he dared not enter London, but he met Fr. Persons and other priests at Uxbridge. There it was determined that Fr. Edmund should use his brilliant pen to write a Latin appeal to the Universities, where his memory was still fresh and in honor. With the enthusiasm which formed such a large part of his character, he chose for his subject, "Heresy at its wits end," and, though the idea seemed a strange one at a time when heresy was the master of the whole material power of the realm, the Father insisted that its very activity and cruelty showed that it had no better argument to produce. The two Fathers renewed their vows, heard each other’s confessions, and then again bade good-bye.

Campion's Rationes Decem

Campion wrote his Ten Reasons (Rationes Decem) to explain why the Catholic faith was the true continuation of the ancient Christian faith and why the reformed religion of Protestantism could not claim to be the true faith. This is one of few surviving copies of the Rationes Decem and is at Campion Hall Oxford.

Campion's Rationes Decem

The ten reasons are listed on the lefthand page.

Fr. Campion, as had been resolved, made his way towards Lancashire, the road beset by ever-increasing perils, while Persons betook himself to London to plan some way of setting up a press to print the work as soon as it should be ready, and other controversial books. Guided as before by some dauntless gentlemen, Father Campion went northward by Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire to Yorkshire, where in the shelter of Mr. Harrington’s house at Mount St. John, amidst the picturesque hills above Thirsk, he stayed some twelve days to work at his promised book, known by the name of the "Ten Reasons." One of Mr. Harrington’s sons was so struck with his father’s guest, that he left friends and home to study at Douay, and returned to be martyred at Tyburn. When Father Campion reached Lancashire he preached assiduously, people of high station passing the night in barns to secure a place to hear his morning sermons. All felt the attraction, not so much of his wonderful eloquence and cultured accent, but of his earnestness and of a hidden power which they knew came from above. While staying at Blainscough Hall, the home of Mr. Worthington, whose wife was a niece of Cardinal Allen, the pursuivants got on his track, and would have seized him, if a maid-servant, in a pretended fit of anger, had not pushed him into a miry pond. The mud served as an effective disguise.

Drawing of Stonor House

Where Robert Persons and Edmund Campion had their secret printing press in the attics. It was on this press that Campion's Rationes Decem was printed.

A safe place had been found for the printing press at Lady Stonor’s at Stonor, near Henley-on-the-Thames; and Father Persons, who was anxious that Father Campion should superintend the "Ten Reasons" as it passed through the press, recalled him to the south, with orders not to stay at any private house, but only at the inns, in order to avert suspicion. While the book was being printed, Fr. Campion evangelized the neighborhood, and passed the anniversary of his arrival in England, St. John’s day, 1581, at Twyford, in Buckinghamshire.

The University Church of St Mary the Virgin, Oxford

These are the pews where Campion left 400 copies of the Rationes Decem to be discovered at the Commencement Day ceremonies on 27th June 1581.

On the 27th of that month of June, when the dons and students entered St. Mary’s, Oxford, for Commemoration the Church served, in those days, the purpose of the Theatre - they found on the benches copies of the new work, while others were distributed up and down the colleges by a priest of the name of William Hartley, who in 1588 gave his life for the faith. "Nothing else is wanting," wrote Fr. Campion to his new Father General and old friend, Fr. Aquaviva, on July 9, "to the cause of Christ than that, to our books written with ink, others should succeed, which are being daily published, written in blood."

The "Ten Reasons," and its audacious publication, only added heat to the raging persecution. Once more Father Campion bade good-bye to his companion and superior, after they had mutually renewed their vows and been to confession, and, early in the morning, they mounted and so parted, Father Edmund with Brother Ralph Emerson, for Lancashire and thence for Norfolk, Father Persons returning to London. He had given orders as before, that Campion should not visit gentlemen’s houses on his way. But a letter reached Father Edmund on the road from Mr. Yates, of Lyford Grange, in Berkshire, then a prisoner in London, to beg him call on his wife and a few Brigittine nuns who happened to be at his house. The Father rode after his superior to obtain leave to go. Father Persons reply was, "I know your easy temper. You are too soft to refuse anything that is asked of you. If once you get there, you will never get away." He allowed him to go, but limited him as to time, and putting him under obedience to Brother Ralph, they parted. So after dinner the next day Father Campion left Lyford. But a large party of Catholics came that very afternoon to visit the nuns. Grieved to have missed the Father, they persuaded Blessed Thomas Ford, one of two priests staying at the Grange, to ride after him and bring him back. Mr. Ford came up to Father Campion in an inn not far off Oxford, and found him surrounded by a number of students and masters of the University, who were trying in vain to get him to preach to them. The arrival of Blessed Ford was soon known, and one and all urged his request, as they hoped thus to share in the privilege of hearing Campion. But he would not yield, yet at last being hard pressed, melting into tears, he said he was under obedience to Brother Ralph. So they all turned on the Brother; who, in turn, overborne, agreed that Father Campion should return to Lyford, while he went off to Lancashire to get the Father’s papers, and that they should afterwards meet in Norfolk. This weakness, on Brother Emerson’s part, was to him a subject of lifelong regret.

Drawing of Lyford Grange

Where Edmund Campion was betrayed and captured on 17th July 1581.

What was known to a large number of University men could not long remain a secret, and there was a traitor about, anxious to gain pardon for crime, by the capture of Father Campion, On Sunday morning, the 16th of July, the nuns, the students, and Catholics, altogether 60 in number, with two priests, and Eliot, the spy, were present at the Father’s Mass, and at his touching sermon on the Gospel of the day Jesus weeping over Jerusalem. Never had he preached as then. Campion intended to leave as soon as dinner was over. But the meal had hardly begun before a man on the look-out announced that the house was entirely surrounded by armed men. Before getting admission, Eliot had learned that his prey was there, and had sent orders to a magistrate to come with a hundred men to do the Queen’s bidding. Father Campion wished to give himself up at once to save the rest, but the two priests hurried him off to one of the many hiding-places, in the hollow of the wall, over the gateway. There, on a narrow bed, the three just managed to stow themselves away, preparing, by mutual confession and earnest prayers, for their fate. The stout Berkshire yeomen did not like the dirty work of invading the home of a neighbor, and, at Eliot’s bidding, of upsetting the whole house. They sought the whole afternoon in vain and when at last they withdrew, vented their annoyance on Eliot.

The Lyford Grange Agnus Dei

An Agnus Dei was a wax tablet bearing the impression of the Lamb of God (Agnus Dei). It was a token of peace and communion sent from Rome to Catholic communities many miles away. This Agnus Dei was discovered in the attics at Lyford Grange in 1959 and given to Campion Hall Oxford. It bears the arms of Pope Gregory XIII who sent Campion and other Jesuits to England.

Drawing of the Agnus Dei found at Lyford Grange

The wretch pretended that his warrant gave him authority to break down the walls, and insisted on returning. The priests were already being congratulated on their escape, and had to beat a second retreat. Mrs. Yates, the lady of the house, remonstrated with the magistrate at her night’s rest being interrupted, and the gentleman politely promised she should not be disturbed; so she had her bed made up in the room next to where Blessed Campion lay hid. She ordered the searchers, when they were tired, to have a good supper served them, and they were soon all fast asleep. Then Mrs. Yates insisted on hearing a fresh sermon from Father Campion, and he was eloquent as ever. All prudence seems for the moment to have been forgotten, and the sentinels posted at the door were up and gave the alarm. But in a moment all was still again. The hunted priests had regained their hole. Next morning, however, the search was renewed. Eliot noticed a wall which was as yet unbroken, and one of Mrs. Yates servants, who was by his side to mislead him, betrayed his alarm by the ashy paleness of his face. In another moment a hammer crashed through, and the three priests were disclosed.

Brother Ralph, they parted. So after dinner the next day Father Campion left Lyford. But a large party of Catholics came that very afternoon to visit the nuns. Grieved to have missed the Father, they persuaded Blessed Thomas Ford, one of two priests staying at the Grange, to ride after him and bring him back. Mr. Ford came up to Father Campion in an inn not far off Oxford, and found him surrounded by a number of students and masters of the University, who were trying in vain to get him to preach to them. The arrival of Blessed Ford was soon known, and one and all urged his request, as they hoped thus to share in the privilege of hearing Campion. But he would not yield, yet at last being hard pressed, melting into tears, he said he was under obedience to Brother Ralph. So they all turned on the Brother; who, in turn, overborne, agreed that Father Campion should return to Lyford, while he went off to Lancashire to get the Father’s papers, and that they should afterwards meet in Norfolk. This weakness, on Brother Emerson’s part, was to him a subject of lifelong regret.

Very unwillingly Mrs. Forster, the sheriff of the county, received orders to send Fr. Campion, with the two priests and some of his audience, on to London. Eliot, full of his success, rode in triumph at their head. Oxford men came out to see him as he passed through Abingdon; and at Henley, Fr. Persons sent his man to note how the Father bore himself, for his friends would not let him go himself.

Campion Taken Prisoner to London

Campion was betrayed and arrested at Lyford Grange in Oxfordshire on 17th July 1581. On the journey to London and imprisonment in the Tower of London, he was made to wear a sign which read "Campion, the seditious Jesuit."

At Colebrook, orders arrived that Campion should make his entry into town on Saturday when the streets would be crowded with market folks, and the prisoners, who had been hitherto treated as gentlemen, now had their elbows pinioned behind their backs, their hands tied in front, and their feet fastened beneath their horses bellies; while to the Father’s hat was attached, the fashion with perjurers in those rough days, a paper on which was written in large letters, "Campion, the seditious Jesuit." So on July 22, all round the crowded streets and squares of the metropolis, the cavalcade of scorn was led till the jaws of the fatal Tower received its victims. Father Campion bade his guards a kindly good-bye, cheerfully forgiving any wrong they had done him, and assuring them he sorrowed more for their state than for his own. He had already forgiven Eliot as freely and as forcibly: "and absolution, too, will I give thee, if thou wilt but repent and confess; but large penance thou must have."

Campion Before Queen Elizabeth I

Tradition has it that Campion was secretly brought before Queen Elizabeth I following his arrest in July 1581. He certainly gave the scholar's address at the age of 13 before Queen Mary on 3rd August 1553, and debated before Queen Elizabeth in Oxford in 1566.

The governor of the Tower, Sir Owen Hopton, thrust his victim into the wretched hole so well named, "Little Ease." But, four days after, July 25, Blessed Campion was taken to the water side, to the house of the Earl of Leicester, and there for the first time since the festivities at Woodstock, found himself face to face with the royal favorite, and his royal mistress, who was accompanied by the Earl of Bedford and the Privy Councilors. They told him they found no fault with him save that he was a Papist; "And that," he answered with deep respect and enthusiasm, "is my greatest glory." Queen Elizabeth offered him life, liberty, riches, honors, anything he might ask, but at the price of his soul. We can imagine his answer. When taken to the Tower, Hopton at once caught his cue. He treated the Father with all consideration, while he suggested to him that the highest honors at court; even the broad lands and miter of Canterbury were within his reach if he would but give way; and Sir Owen spread the news abroad that Campion had accepted the bribe. When, however, the offer to become a Protestant was made openly to him, he treated it with such scorn that it was at once resolved to have recourse to torture.

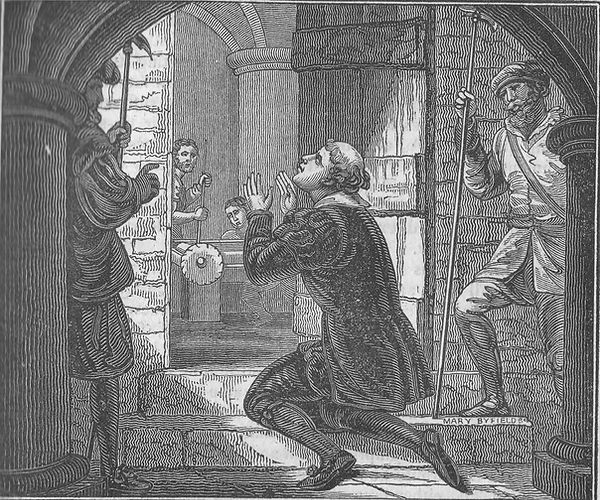

Campion Going to the Rack

Engraving (1830s?) by Mary Byfield from Memoirs of Missionary Priests (1741) by Bishop Richard Challoner. Campion was subjected to violent torture including his limbs being streteched and wrenched on the rack. Before entering the room of his torture, he would kneel to pray.

It was probably on the day, on which St. Ignatius had died, July 31, that Father Campion first tasted the horrors of the rack-chamber. He knelt on the threshold, and made the sign of the Cross, and, as they stripped him and bound him to the rollers, called on Jesus and Mary for help. No voice could come up from that subterranean hell: but it was noised about London that Campion was yielding, that he had betrayed his friends, and that he would soon openly become a Protestant. That some of his companions, under the awful torture of strained muscles and dislocated limbs, had told some secrets, seems too clear; but Burleigh was obliged to own, in a confidential letter to Lord Shrewsbury, that from Campion they could exhort nothing of moment.

Campion on the Rack

Engraving by Giovanni Cavallieri after Niccolò Circignani from Ecclesiae Anglicanae Trophaea (Rome 1584) Houghton Library, Harvard University

But the slander did its work for the time. Mr. Pound wrote to the Father to implore him to say what truth there was in the awkward rumors afloat. Campion was allowed to receive the letter and to send a reply, but both were intercepted, and it was said that in the answer, though he had, in weakness, confessed to some of the houses at which he had stayed, he had discovered nothing of secret, nor would he, "come rack, come rope." The great aim of Elizabeth’s advisers was to connect Campion, rightly or wrongly, with the schemes afloat of foreign invasion or home treason, from which, both by natural inclination and by the express orders of his superiors, he had kept carefully aloof. As he never was allowed to confront those whom he was said to have accused, it became evident, that even if the words of his letter to Pound were truly given, he meant nothing more than that he had never divulged anything that his torturers did not know before.

The European fame of Campion, the extraordinary renown his "Ten Reasons" had won him, from friend and foe, made Burleigh and Cecil feel they could not treat him like an ordinary priest or recusant unless they could first damage his credit as a scholar. Nine Deans and seven Archdeacons were told off to answer the book which they affected to despise. But now that the author was in their clutches, after the prison dietary, the rack, the sorrow of heart, there did seem a chance that he might fail to maintain the challenge he had made to support his faith against all comers. So the servile Bishop of London was ordered to prepare a series of public discussions. In the venerable Chapel of the Tower, without a book to aid them, without even a chair-back to rest against, BB. Campion and Sherwin, with other Catholic prisoners, were brought face to face with the Deans of St. Paul’s and Windsor, and other disputants, who were seated at a table, supplied with any number of works of reference. A Catholic who was there tells us that Father Edmund looked ill and weary, his memory nearly gone, his force of mind almost extinguished. Yet he won admiration from all by his ready answers, by his patience under the coarse abuse and ill-timed jests of his well-fed and well-prepared adversaries. They jeered at his ignorance of Greek, a false reproach which in his humility he accepted in silence; they denied his quotations from Luther, because they could not find them in their emended edition; they threatened him with torture and with death. In spite of the odds against him, there was no doubt which way the victory inclined. What with Campion’s saintly meekness and his unanswerable arguments, the Venerable Philip Earl of Arundel owed his after conversion to what he then saw and heard, when from a Protestant and a courtier of the voluptuous Queen he became a confessor and a martyr of the faith. Each fresh discussion, and there were four in all, proved more fatal to the Protestant cause; and when at length his enemies determined they should cease, spite of the boasting of the sleek dignitaries of the new creed, it became clear to all that Campion had been neither traitor to his friends, nor would be to his God. His success was sung in doggrel rhymes in the streets –

Let reason rule and racking cease,

Or else for ever hold your peace;

You can’t withstand God’s power and grace,

No, not with t Tower and racking place.

As it had been decreed by the Queen’s Counsel that Father Campion must die, false witnesses were now suborned, as a last resource, to prove his share in the schemes by which outraged Europe hoped to tear Elizabeth from the throne. But when neither rack nor perjury could entrap him, an imaginary plot had to be trumped up. The rack, which he had declared was more bitter than death, was again applied to exhort a confession from Father Campion, and with such savagery that he thought they meant to kill him then and there. Still, as Lord Hunsdon said, they might sooner pluck his heart out of his breast, than wring one word from him against his conscience. When the jailor asked him next day how he felt his hands and feet, his answer was, "Not ill, because not at all."

At last the indictments were drawn up. It mattered little what they were, for the Crown lawyers had their orders to carry a conviction at any cost and in any way. So on Tuesday, November 14, the grand old Hall of Westminster, the scene of many of the greatest trials in English history, saw Blessed Campion, with Blessed Cottam and Fr. Bosgrave of the Society of Jesus, BB. Sherwin, Kirby, and Johnson, with Rishton, a priest, and Orton, a layman, brought up before the Grand Jury. When the indictment had been read, Father Campion, who was the spokesman all through the trial, protested before God and his holy angels his innocence of any treason, and Sherwin added, "The plain reason of our standing here is religion and not treason." When called upon to plead, one of the prisoners had to lift up B. Campion’s tortured arm, made helpless by the rack, which he did, reverently kissing it, as the martyr stoutly answered, "Not guilty." Next day Blessed Briant of the Society of Jesus, BB. Richardson, Shert, Ford, Filby, with two other priests, Hart and Colleton, were brought up to plead to the same indictment.

St Alexander Briant SJ

who was martyred with Campion at Tyburn on 1st December 1581

The trial commenced on Monday the 20th, if trial that could be called, which Hallam stigmatizes as "unfairly conducted, and supported by as slender evidence as any perhaps that can be found in our books." The Chief Justice, Wray, who presided, was a Catholic at heart, and the shameless travesty of justice in which he took an unwilling part, is said to have shortened his days. Skillfully, but hopelessly, for three hours the arguments of counsel and the perjuries of degraded witnesses were met and answered by Fr. Campion, and the verdict was given to order after an hour’s debate. When asked what he had to say why he should not die, with his face beaming and with noble dignity, the eloquent martyr replied, "It was not our death that we ever feared. But we knew that we were not lords of our own lives, and therefore, for want of answer would not be guilty of our own deaths. The only thing that we have to say now is that if our religion makes us traitors, we are worthy to be condemned; but otherwise are, and have been, as true subjects as ever the Queen had. In condemning us you condemn all your own ancestors all the ancient priests, bishops, kings all that was once the glory of England the island of Saints and the most devoted child of the See of Peter. For what have we taught, however you may qualify it with the odious name of treason, that they did not uniformly teach? To be condemned with these old lights not of England only, but of the world by their degenerate descendants, is both gladness and glory to us. God lives, posterity will live: their judgment is not liable to corruption, as that of those who are now going to sentence us to death." No wonder Blessed Cottam said he was quite willing to die, after hearing Campion speak so gloriously.

Then the hideous sentence was pronounced, and Campion made the oaken rafters ring with a jubilant "Te Deum laudamus, Te Dominum confitemur,"(The Little Lord) while B. Sherwin responded, "This is the day which the Lord has made, let us exult and rejoice in it," and such a chorus of praise and joy rose from the dock as astounded and touched the vast throng. The prisoners who had been arraigned on the second day were brought up for like judgment on the Tuesday.

Cruel treatment and heavy irons awaited the Blessed Campion on his return to the prison. But nothing could alter his gentle patience. A week after his sentence, his sister brought him the offer of a rich benefice if he would but change his religion. He proffered Eliot, his betrayer, now a yeoman of Her

Majesty’s guard, who came to visit him and express his sorrow at his fate, a recommendation to a Catholic Duke in Germany, in whose territory he could live in safety should his life be menaced by Catholics as he feared. This charity converted Campion’s jailor. The martyr prepared for death by a five

days fast, and spent the two last nights, Wednesday and Thursday, 29th and 30th of November, in prayer. Out of the condemned, three victims were selected for the first sacrifice, Campion the Jesuit, Briant of the Rheims College, and Sherwin of that of Rome.

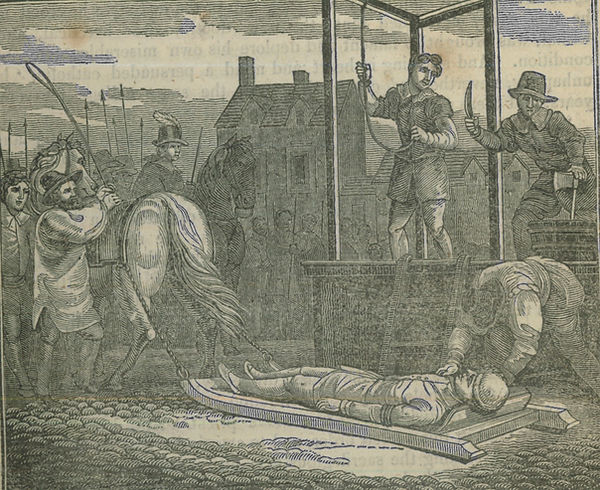

The Martyrdom of Edmund Campion, Alexander Briant and Ralph Sherwin

Engraving by Giovanni Cavallieri after Niccolò Circignani from Ecclesiae Anglicanae Trophaea (Rome 1584) Stonyhurst Collections

It was in a dreary downpour that, on December 1, the three were brought out to be tied on two hurdles, each of which was fastened to the tails of two horses. BB. Sherwin and Briant were bound to one, Campion to the other. As they were dragged through the mud and over the stones of the unpaved streets, a mob of ministers and fanatics followed them, calling on them to be converted. Still the Catholics had from time to time a chance to speak to them, and a gentleman like another Veronica, wiped the mire from B. Campion’s face. As they passed beneath the New Gate, where now the prison stands, Campion tried to raise himself -"Moriturus te saluto"(are about to die, salute)- to pay homage to the statue of Our Lady that had escaped the iconoclasts’ hammer in the niche above. The crowds grew denser, as at the end of the long road the gallows came in sight. The martyrs’ faces were bright as the sun shone out. "They are laughing," the people cried, "they do not care about death." A new gibbet had been put for the Blessed Dr. Storey’s death. The blood of a martyr had hallowed the cross. Close to the triple tree was a group of noblemen on official duty, but many a Catholic gentleman and even a priest pressed up to witness the sacrifice. Father Campion was the first who was made to get into the cart which stood beneath the gallows, and then he put, as he was bid, his head into the noose. And, when the buzz of the thousands ceased, he began gravely, "Spectaculum facti sumus Deo et Angelis, et hominibus: We are made a spectacle or a sight unto the Lord God, unto His angels, and unto you men/ verified this day in me." The sheriffs bade him confess his treason against the Queen, but he only reiterated his innocence, saying, "If you esteem my religion treason, then I am guilty; as for other treason, I never committed any." So, too, he explained, that the only secret he had kept back under torture, was merely the fulfilment of his priestly functions. So for some time he stood in earnest prayer, oftentimes interrupted by captious questions. A minister would have had him to pray with him. "You and I," he replied, "are not one in religion; wherefore, I beg you to content yourself. I bar none of prayer, but I only desire those of the household of the faith to pray with me, and in mine agony to say one ‘I believe.’ " Then they bade him to sue for the Queen’s forgiveness, and to pray for her. "Wherein have I offended her? In this I am innocent. This is my last speech; in this give me credit. I have prayed, and do pray for her." "For which Queen?" broke in Lord Charles Howard. "For Elizabeth, your queen and my queen, unto whom I wish a long, quiet reign with all prosperity." And so the cart was drawn away, and a long groan went up from the crowd. The body swung in the air till life was extinct. As it was cut down and quartered on the block, a drop of blood and water splashed out on young Henry Walpole, and in an instant he felt himself called to be a Catholic, and, in due time, to be a Jesuit and a martyr.

The engraving above shows a man being drawn on a hurdle to Tyburn for execution. The hurdle was like a sledge; the victim was bound head downwards and dragged through the mud and filth of the streets while the crowds spat and jeered.

Sherwin, proto-martyr of the English College, was the next to die. And, last of the three, Father Briant, freshly dedicated to God in the Society of Jesus, whose beautiful young face, lit up with desire of martyrdom, won the hearts of all who stood by.

It was not until the 28th and 30th of May following, that the other Blessed Martyrs, who had been condemned with Campion, met their deaths at Tyburn. As they had all stood together at the bar of human injustice, at Westminster, so they all met together again in Heaven, to receive from Divine Justice the unfading crown amongst the white-robed army of martyrs.

Campion's Rope

This is the rope used to bind Edmund Campion to the hurdle (see right) on which he was dragged through the streets of London to the place of Execution at Tyburn. The rope was recovered by Fr Robert Persons SJ and worn by him as a belt until his death. The major piece of this relic is kept at Stonyhurst College. Small sections of the rope were given to St Francis Xavier Church Liverpool, to Campion Hall Oxford at its foundation, and to the Vatican Collections on Campion's canonization in 1970.

"FOR BEHOLD FROM HENCEFORTH ALL GENERATIONS SHALL CALL ME BLESSED!"

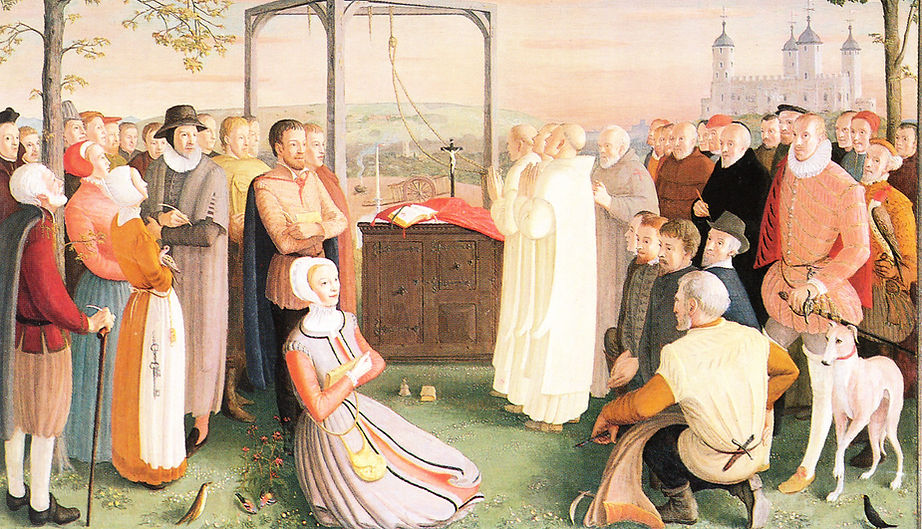

The English and Welsh Martyrs

Painting by Daphne Pollen (1904-86) commissioned for the 1970 canonization of the forty martyrs of England Wales.

THE ANNUNCIATION

Lowliest of women, and most glorified!

In thy still beauty sitting calm and lone,

A brightness round thee grew and by thy side

Kindling the air, a form ethereal shone,

Solemn, yet breathing gladness. From Her throne

A queen had risen with more imperial eye,

A stately prophetess of victory

From her proud lyre had struck a tempest’s tone,

For such high tidings as to thee were brought,

Chosen of Heaven! that hour: but Thou, O Thou!

Even as a flower with gracious rains o’er-fraught,

Thy virgin head beneath its crown didst bow,

And take to thy meek breast the all Holy Word,

And own thyself the Handmaid of the Lord.

- Mrs. Hemans

Campion Flower

The Red Campion (Silene dioica) is associated with St Edmund Campion and often appears in coats of arms of institutions dedicated to him (such as Campion Hall, Oxford).

THE SONG OF THE VIRGIN

Yet as a sun-burst, flushing mountain snow,

Fell the celestial touch of fire ‘ere long

On the pale stillness of thy thoughtful brow

And thy calm spirit lightened into song.

Unconsciously perchance, yet free and strong

Flowed the majestic joy of tuneful words,

Which living hearts the choirs of Heaven among

Might well have linked with their divinest chords,

Full many a strain, borne far on glory’s blast

Shall leave where once its haughty music passed,

No more to memory than a reed’s faint sight;

While thine, O childlike virgin! through all time

Shall send its fervent breath o’er every clime

Being of God, and therefore not to die.

- Mrs. Hemans

St Robert Southwell SJ

Jesuit priest, poet and martyr

Died at Tyburn 21st February 1595

Feast Day: 1st December with Edmund Campion SJ